This is the first of a series of blog posts I am writing as the Executive Director of Interfaith Community Shelter. My hope is these posts will be beneficial if you’re concerned about homelessness in our country and our community. We all need better understanding of what brought us to where we are.

The national roots of homelessness date back 50 years.

We didn’t arrive overnight or by accident at this crisis. Numerous changes to social welfare programs in the U.S., as well as some poor political and policy decisions, got us here.

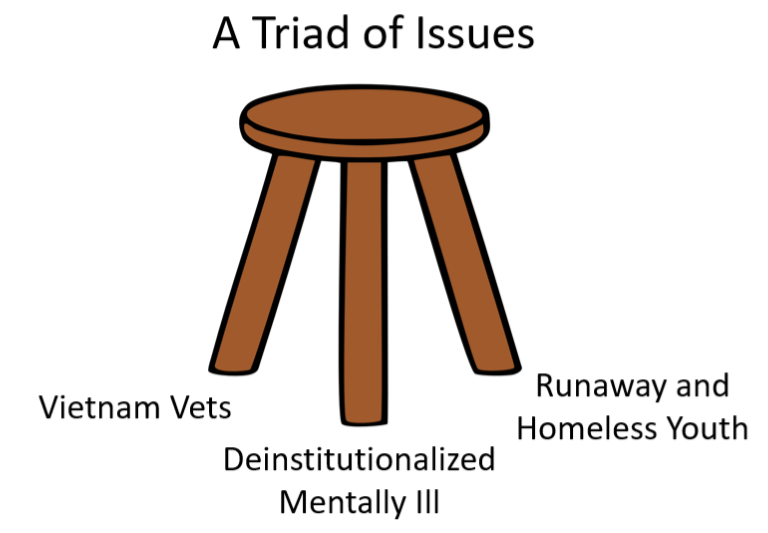

When I talk publicly about my job, I describe the historical roots of the homelessness crisis as a three-legged stool. Vietnam War veterans made up the first leg. De-institutionalized mentally ill individuals were the second. The third leg of the stool were runaway and homeless youth fleeing abuse. In the process, they often lost their homes.

Our story starts in the ‘60s and early ’70s. Major changes to the 1960s Great Society social safety net took less than a decade to unravel that net.

The origins of today’s crisis

We as a society still haven’t grappled with the outcomes.

As shelter operators in the 1980s, we quickly discovered that we weren’t prepared to serve the homeless

populations that we actually began to see. We had been prepared to serve people in short-term bad luck or financial crisis. These were the people that the first homeless shelters were designed to serve. Maybe you lost your job, or had to make a car payment over rent and got evicted. We envisioned functional people with financial problems to solve.

Instead, what we got were people reeling from untreated mental illness or severe trauma. Let’s talk now about one subset —Vietnam War vets who returned home from war deeply traumatized.

The frontal lobe of the brain is responsible for judgment, decision- making, reasoning, problem solving and impulse and emotional control. We now know that the adolescent brain does not fully mature until we reach 25 years of age. Men drafted into World War II (1941-45) were age 27 on average. Vietnam War draftees were on average 19.

They set the stage for the recognition of PTSD or untreated post-traumatic stress disorder as an actual mental health affliction.

PTSD can damage the frontal cortex which already had not sufficiently developed in these young men returning from Vietnam. PTSD generates flashbacks, hyper-vigilance, guilt and anxiety. Vets find it difficult to maintain relationships, or hold onto stable employment and housing. Once they become homeless their lack of emotional response control can cycle into a mental health crisis. It often does. Severe PTSD-related mental health issues for veterans persist.

But the Veterans Administration—the federal agency tasked with helping returning vets—couldn’t support Vietnam War combat re-entries, because PTSD wasn’t an official mental health diagnosis until 1980.

We saw Vietnam veterans, when I first started working at Interfaith Community Shelter–Pete’s Place, who felt the VA wasn’t responsive to their needs. They wanted nothing to do with the agency. This lasted as an attitude despite positive changes at the VA that could have benefited these Vietnam vets.

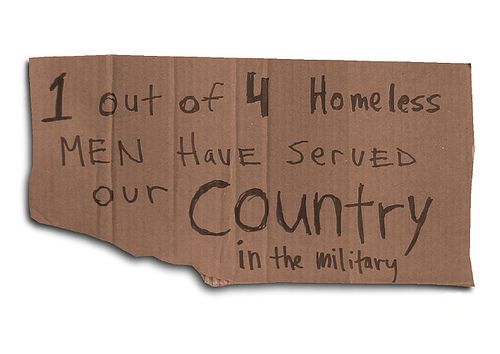

This first leg of the stool–veterans experiencing homelessness–shows the origins of the problem. Many veterans experience homelessness today. 17 veterans commit suicide every day in the U.S. That staggering number is higher than troops lost in combat.

Thank you for sharing this information. The homeless are my brothers and sisters in Christ. I want to help, but I don’t know what is the best/right thing to do. Awareness is an important first step. I look forward to learning more.

Thanks Joann for your comment. I am excited to share a lot of the insights I’ve gained in upcoming posts. We hope this is just the first step in generating constructive community conversations. Please share widely with your networks.