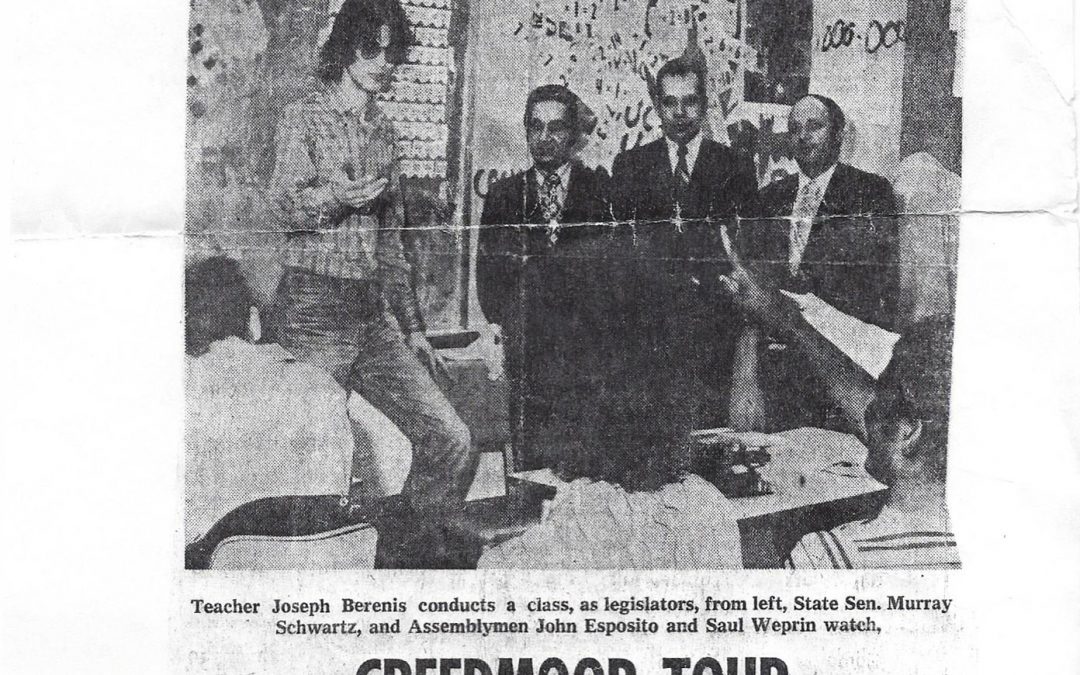

Recently, I was doing some spring cleaning and came across a newspaper article with a photograph of me in the now defunct Long Island Press from the 1970s. I was working at Creedmoor State Hospital, one of those state mental institutions in New York with a horrific reputation for abuse. It was the beginning of what was referred to by politicians and homeless advocates as “decentralization” and then, later, “de-institutionalization.”

The article was reporting on members of the New York State Legislature, both from the Senate and Assembly, who were visiting Creedmoor because the neighbors were complaining about people with mental illness being released into their community.

Sound familiar?

Here we are 50 years later, and we still face the same issue across the country and in Santa Fe. A large percentage of people who are homeless have been rendered so by a mental health issue. And because the Interfaith Community Shelter is a “come-as-you-are” shelter, that percentage is even greater than for shelters that have stricter requirements for entry into their programs.

I’ve being doing this work for decades. No matter where I worked, every time we tried to open a shelter in a particular community, whether its leadership was Democrat or Republican, it was the same old mantra: “I support what you’re doing, but not here.”

If not here, then where? Why can’t communities see those with mental health issues as neighbors who need their help and added support?

There is a communitarian movement in San Francisco, where neighbors do help support and care for those who are homeless and camped out in their neighborhoods; where people “draw on shared identities to serve individuals.” This concept is beneficial to the person who is homeless, but, importantly, it also benefits the person who isn’t. It reduces the stigma associated with both mental illness and homelessness.

The issue I often hear most about when it comes to opening a shelter for homeless people is that the value of homes in adjoining neighborhoods will depreciate. But is this actually true? Back in 2014, this issue repeatedly arose with Pete’s Place neighbors, but the real estate market was still in the doldrums, and everybody’s home value had depreciated. However, the home values argument begs the larger question: are home values more important than the value of a fellow human being? Does present day capitalism preclude compassion?

John Kenneth Gailbraith wrote about the “newly rich,” (as opposed to those with “old money from the mid-twentieth century who felt an ethical and moral obligation to contribute to their fellow citizens in need) as engaging in “one of man’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy, that is the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness.” He went on to point out that “it is an exercise which always involves a certain number of internal contradictions and even a few absurdities.”

If we have learned anything from the coronavirus pandemic, it is that the survival of others depends on all of us meeting our own moral and ethical responsibilities; that if we happen to pass someone on the street without wearing a mask, we could easily infect another person without even knowing it; that selfish acts can have life-altering consequences for others. No matter how much we believe in individualism, we cannot escape the fact that our individual decisions have real consequences for the community as a whole. Selfless acts of kindness and compassion have ripple effects throughout our community, because we are all in this together. We are “communitarians,” whether we like it or not.

I recognized you immediately in that old photo, Joe. Good article. I miss my more direct connection with Pete’s Place. Thanks for everything you do.

Wow, Joe! That photo certainly exemplifies the divide over the last 50 years, where “the suits” are observers of the plight of the people — and many of them can’t quite get what the real need is. We don’t see Jimmy Carter appear in a suit too often! And look at what he has done to change homelessness to homeownership. I don’t know what Santa Fe would be like without the shelter at Pete’s Place!! Thanks for continuing your work with our most vulnerable population during this crisis time.