Runaway and homeless youth make up the third leg of the three-legged stool I’ve been describing. In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, young people who were part of the hippie generation started crisscrossing the country — often in protest of their parents’ lifestyle, which they saw as staid and conformist.

During this time, a group of youth advocates in Washington D.C. lobbied Congress to set up a network of safe homes or youth hostels in order to keep these kids protected and safe. But Congress, in its inimitable way, chose to do nothing.

During this time, a group of youth advocates in Washington D.C. lobbied Congress to set up a network of safe homes or youth hostels in order to keep these kids protected and safe. But Congress, in its inimitable way, chose to do nothing.

Then, in 1972, John Wayne Gacy began a six-year crime spree of sexually abusing and murdering boys, some of whom he picked up at local Greyhound stations in Illinois. Police eventually discovered 33 bodies of boys and young men on his property, 26 of them buried in the crawl space. Almost simultaneously, Dean Arnold Corll murdered 28 teenage boys in Houston, Texas. Those crimes were known as the Houston Mass Murders. That was when Congress agreed to do something. In 1974, they passed the National Runaway Act, which provided funds to establish a network of youth shelters all across the country.

That made it possible for young people under the age of 18 to stay in a shelter for 30 days without parental permission. “Without parental permission” was the key to their safety, in many cases, as many of the runaways were fleeing abuse and neglect. In 1977, Congress amended the law to be the National Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (RHYA).

However, by the 1980s, the social landscape had changed dramatically, and the guitar strumming, highway-roaming hippie became a dinosaur–extinct.

Similarly to how #MeToo suddenly gave women permission to talk about abuse that had been happening for decades—and to be believed—growing understanding about child abuse in the early 1980s empowered young people to talk about the abuse going on in their homes or family. Soon, local teenagers seeking refuge and safety from sexually and physically abusive situations filled the youth shelters.

I remember one of the first young girls to show-up at the youth shelter in Woodstock, NY, where my career began.

She had been victimized sexually. One day, I watched as her mother and two aunts stood in my office trying to convince her to come home. She stood steadfast and refused to go, even after her mother said, “Grandpa did it to us, too,” implying that the behavior was okay.

At the time, we had no real understanding of how emotionally devastating victimization could be. As shelter operators, we had to seek the help of the local mental health services department. There were other difficulties helping homeless youth. Before the McKinney-Vento Act, young people in homeless shelters could not be enrolled in school and often missed out on long periods of education they would never regain, further alienating them from society and contributing to chronic homelessness.

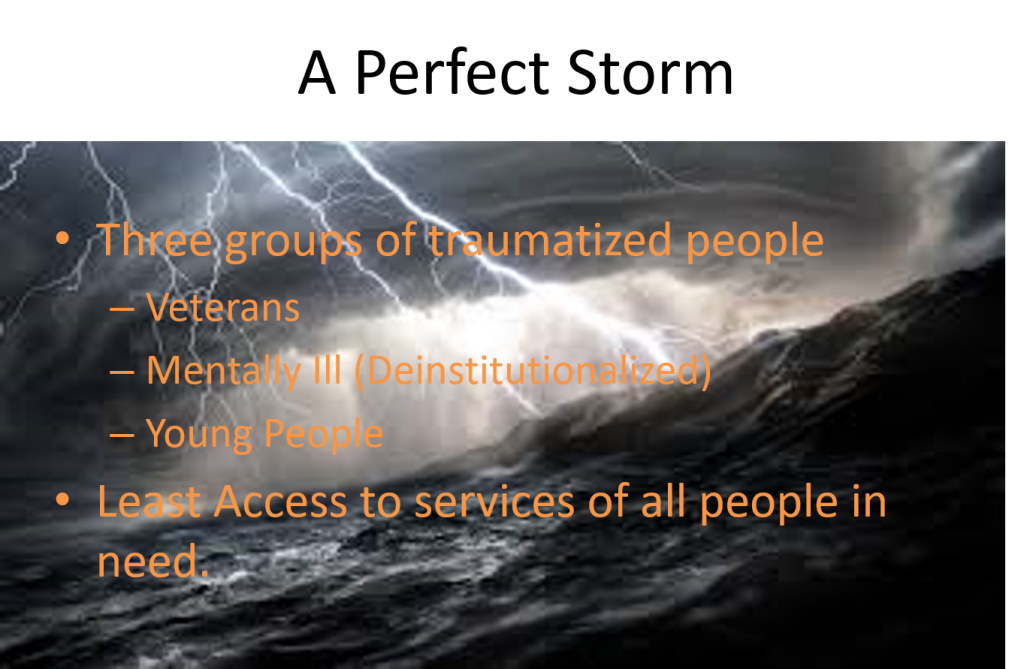

The early 1980s were a perfect storm, as I’ve reported in these posts. Three groups of traumatized people we’d never seen before (and didn’t know how to help) began arriving at our nation’s shelters: Traumatized veterans; de-institutionalized people suffering from mental health issues; and victimized youth.

The early 1980s were a perfect storm, as I’ve reported in these posts. Three groups of traumatized people we’d never seen before (and didn’t know how to help) began arriving at our nation’s shelters: Traumatized veterans; de-institutionalized people suffering from mental health issues; and victimized youth.

Since then, not much has changed.

Our country still lacks a mental health infrastructure to deal with the rampant opioid and methamphetamine epidemics. Income inequality makes an ever-widening gap between the haves and have-nots. There’s still not nearly enough affordable housing as our country wages an endless cycle of wars. One might say that the situation that underpins the homeless crisis has only gotten worse.

Thank you for being there for me when no one else was ❤️

When is the truth about the boys who were victims of sexual abuse upon the highways of America during the 1970s going to be told? Tens upon tens of thousands of those boys.